Background

Since the dawn of the internet, increased connectivity has changed society in many profound ways. But as we grapple with the evolution of information technology, there is one application in particular that now stands above the rest in its potential to save and protect society’s most valuable resource of all: human lives.

Through connected vehicle technology, we now hold the keys to save thousands of lives every year.

Each year in the U.S., as many as 40,000 lives are lost in auto accidents. While landmark safety innovations like the seat belt, airbags and anti-lock brakes have helped reduce the fatal crash rate over time, they fall short of connected vehicles in one critical aspect: they do not address the root cause of auto accidents.

Human error is to blame for 94% of all motor vehicle accidents, according to the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration. So while seat belts and airbags mitigate the impact of a collision, they do little to prevent a collision from happening in the first place. All accidents might be preventable, but only once human error — the decisions a driver makes while on the road — is eliminated from the equation.

This is why connected vehicles represent a watershed moment in the history of automotive safety.

Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), or vehicle-to-everything (V2X) technology enables a car to communicate with its surroundings. Using either dedicated short-range radio or cellular technology, connected vehicles can provide drivers with instant, highly-accurate warnings to impending crash situations. NHTSA estimates this could reduce the number and severity of unimpaired motor vehicle crashes by up to 80%.

The Association of Global Automakers explains how this works in practice:

Just one example: Each car or truck would transmit what’s called a Basic Safety Message to surrounding connected vehicles and traffic monitoring systems. The basic message contains information on where a car is, where it’s headed, and how fast. If it’s about to go through a red light because the driver is distracted, other cars in the area and the traffic signaling system can warn drivers or take other steps to avoid a collision.

Here’s an illustration from the U.S. Department of Transportation:

The 5.9 GHz Safety Spectrum

In order for vehicles to talk wirelessly with one another and their surrounding environment, they need what’s known as the Safety Spectrum — a radio spectrum reserved specifically for transportation safety. In order for V2X to work to its full potential, it needs clear, uncluttered airspace so that wireless signals can transmit instantaneously and unimpeded.

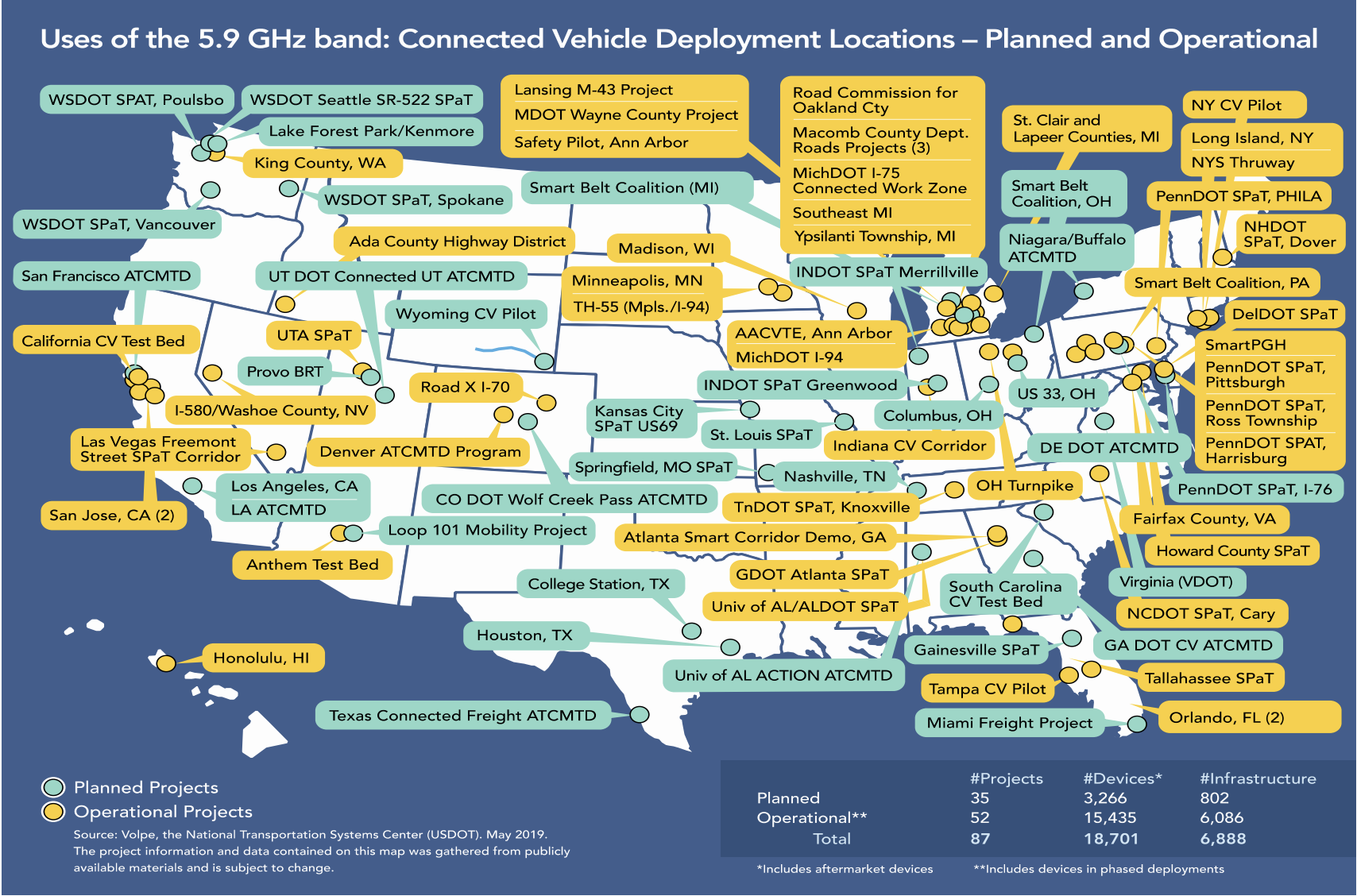

In 1999, the Federal Communications Commission designated 75 MHz of radio spectrum in the 5.9 GHz band to be used for vehicle and infrastructure communications. Since then, auto manufacturers and infrastructure engineers have been working to develop smart technologies that rely on that open window of public airwaves.

The Problem

Last month, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai announced in a blog post his intention to divert 45 MHz — more than half — of the the 5.9 GHz spectrum away from transportation safety for other uses — primarily faster unlicensed WiFi:

In particular, I’ve proposed making the lower 45 MHz of the band available for unlicensed uses like Wi-Fi. Since its launch, Wi-Fi has become a staple of everyday life. Wi-Fi now carries more than half of the Internet’s traffic. It has become a foundational technology for the Internet of Things, connecting our TVs, thermostats, baby monitors, refrigerators, washing machines, toys, and even toilets. We therefore need to make more spectrum available for unlicensed use to meet growing consumer demand.

Rather than preserve the space needed for connected vehicles to communicate unimpeded, Chairman Pai wants to slash it in half to make room for TVs, toys and toilets.

In a speech explaining the proposal, Chairman Pai drew a peculiar analogy likening the Safety Spectrum to a baseball team — the Washington Nationals.

What manufacturers, researchers and developers need for large-scale deployment is certainty from the FCC that the 5.9 GHz spectrum will be preserved for transportation safety. Instead, Chairman Pai is sending mixed signals that threaten to derail this life-saving technological progress.

Automakers have expressed this frustration in testimony before Congress. In a letter to the leaders of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, they explained how FCC directives slowed their development of this technology — only to then blame them for not deploying it quickly enough.

On April 16, 2018, Toyota announced that it would begin deploying DSRC on vehicles sold in the U.S. starting in 2021. On May 10, 2018, two FCC commissioners wrote the company with a warning that the company should be careful “when committing capital expenditures to DSRC technology.” The following April, Toyota announced a pause in deployment, citing uncertainty about federal government support for preserving the Safety Spectrum. FCC commissioners now appear to criticize manufacturers for doing exactly what the agency wanted — not investing in DSRC — and then using that as the justification for reducing the amount of spectrum available for DSRC.

The FCC is scheduled to vote on the proposal on December 12.